Archive

GTP Dialogue with Vinicius Marino Carvalho Part II Historical Problem Spaces and Beyond

This is the second part in a planned series of dialogues with historian, educator, and historical game designer, Vinicius Marino Carvalho, about the Historical Problem Space Framework as set of concepts and tools for analyzing and designing historical games in any medium. (Read Part I)

Vinicius: So, Jeremiah. I think I owe your readers an apology. I ended the first part of our collaborative blog post on a *massive* cliffhanger, promising to introduce a perspective that could in theory render the entire HPS framework moot.

(On hindsight, I really should make a note to tone down on the hubris…) But, more to the point, I think it’s fitting that I explain what I was talking about.

This might sound trivial, but there’s an explicit assumption in the “A.R.T.M.O.”. typology (Agents, Resources, Tools, Metrics and Obstacles) (Jeremiah’s note: it changed from A.R.T.O. to A.R.T.M.O.s for the upcoming book) that these four elements are different things. Meaning: there are entities that act, and entities that are acted upon. Moreover, in history, specifically, we generally assume that agents are human, groups of humans, or at least human-like in some capacity.

Herein lies the rub: there are some theorists who have been trying to problematize the distinction between ‘agents’ and ‘things’. You can find them in perspectives like posthuman theory, actor-network theory, animal history, interspecies history, archaeology (which deals with the agency of things), new materialism (which deals – among other things – with the agency of inanimate matter), etc.

Read more…Paradox Europa IV Universalis Educator Guide is Out (and Free)

I’m very pleased to share Paradox’s Educator’s Guide for Europa Universalis IV (that I wrote) is now available for all. EUIV is a challenging game & I spent considerable time breaking down exactly how I’d use it in history classes in hopes the many interested educators out there will give it a try.

It’s a 3 part guide: Logistics, Student initial play guide, and historical problem space analysis of EUIV. The focus is on the game as history so interested educators can decide what parts they want to focus on and what aspects of the history are more and less problematic in the game.

Hopefully it will be of some use out there. I enjoyed the challenge, and I am very glad to have a worked example out there for educators about how to use the historical problem space framework for teaching. Of course, as always, just reach out if I can help you further or reach out to Paradox.

Gameworld Space and Action-Choices in Historical Games (HPS framework)

Just a quick reminder/introduction. The Historical Problem Space framework is a set of terms and concepts I’ve been developing over the past decade+ to help all intersections of educators and academics analyze historical video games in away that is holistic and recognizes that historical games are both functional as working computer programs (and, to a lesser but still useful extent, analog games) and as cohesive designs. This means any particular historical phenomenon in a game is functionally and cohesively connected to al the rest of the game design.

The framework continues to develop but my most recent core writings on this are:

The Historical Problem Space Framework: Games as a Historical Medium (2020)

Gaming the Past: Second Edition (2022)

And there are links to other articles and talks about HPS on this page

Greetings to all who, like me, find themselves fascinated by historical games,

Not infrequently I find my thoughts well ahead of my writing on the Historical Problem Space framework for historical game analysis (https://gamestudies.org/2003/articles/mccall) (Yes, I’m that sort of person who thinks about games and history games a significant amount of the time) Today I was working out a lecture on 4x games so that my students will have some genre understanding when looking at Colonization and Imperialism (the 4x games — but of course the historical phenomena too). I’ve been referring to the different kinds of action-choices a player agent can make in gameworld space.

I have listed and briefly discussed some of the core action choices a player agent has available in a gameworld space. I thought I had perhaps listed them all in the 2020 article, or perhaps in GTP 2.0 but now I’m thinking the core action-choices in gameworld space should be (helpfully, I hope) set out in one places until I can work them into a published article or book.

So, a quick reminder, the gameworld space is the space in which the player agent (the main playable character) pursues the goals (if they choose) that the developers have set for them and, while doing so, encounter the various elements in the space (a.r.t.o s = non-player agents, resources, tools, obstacles etc). The player agent makes and takes action choices in order to (if they choose) attempt to achieve the goals the developers have designed for the game. The “problem” in the historical problem space design that is standard in historical games, is to solve, avoid, overcome, utilize etc. the elements (a.r.t.o s) in the gameworld space that are keeping the player agent from the designed goals or can help the player agent.

Historical Problem Spaces on the Studying Pixels Podcast

In late September, I had the pleasure of talking with Stefan Simond over at the Studying Pixels podcast about games as historical problem spaces

https://studyingpixels.com/games-as-historical-problem-spaces-with-jeremiah-mccall/

Historical Game Design Theory and Practice: Dialogue with Luke Holmes, Part 2

Part 1 of our dialogue blog is here. Last time, Luke left us with Chris King’s argument that game developers should choose their historical interpretation based on whichever suits the gameplay best. I always felt a bit uncomfortable with that, but maybe I have too much of an agenda as a historian! . We’ll start this second instalment from there.

JEREMIAH: That does seem to be a rather bold statement. Here my response as an educator with historical games and as an academic studying historical games might differ. King’s suggestion works perfectly for a history class so long as the teacher presents the game as an interpretation, a model, that needs to be critiqued for defensibility by students (McCall 2011 and now McCall 2022, forthcoming). I suppose though that even from a more formal academic analysis, the idea of picking a historical interpretation based on mechanics is probably not noticeably different than the practice we mostly all seem to recognize: that in a conflict between fun/playability and historical accuracy (leaving aside how problematic that term can be), devs on record tend to say that they will usually go with fun/playability–I’d have to go back to look for references; pretty confident Sid Meier has said that. Also pretty confident that Soren Johnson agreed and elaborated on this principle back on my first GTP:Designer Talks podcast. In a sense “picking the historical interpretation to suit the game mechanics” is just a variation on this right? Even so, it’s a generalization of course, so whether devs pursue something more on the consistent with historical evidence (“defensible”) or less will depend on their originality pillar, right, to the extent that advancing a certain historical proposition could be part of a game’s originality? (or the expectations pillar if players expect a defensible historical model?)

LUKE: I wonder too if video games’ position in media-culture-hierarchy also gives game devs a lot of flexibility precisely because they don’t have to be defensible. Academics (and a lot of devs, too) would I think argue that video games very much are vehicles of history, but I’m not sure all audiences would agree. When video games aren’t presented as an authority (in the way that a book, museum, or academic might be, however flawed that is) the worry about whether a historical model fairly represents the period or discourse becomes unimportant – it is, after all “just a game”. For me though, games that take this line run a risk of trivializing the past, or even exploiting it for inspiration and genre appeal. It creates a nonsense proposition: that fun is directly incompatible with good history.

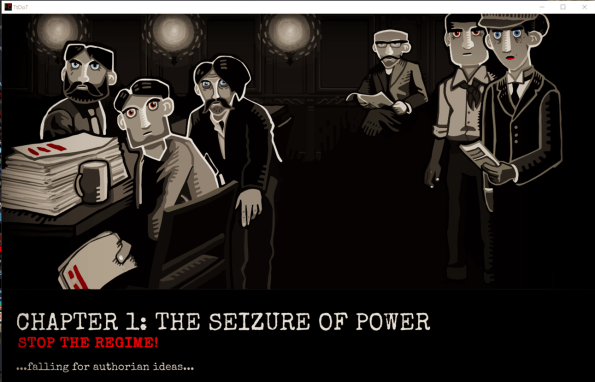

Read more…Through the Darkest of Times’ Historical Problem Space

This is a republication of my two-part essay on Playthepast.org, (original Part 1 and Part 2 here). It is the first long-form historical game analysis I have written using the Historical Problem Space framework. The first half of the essay is more descriptive, illustrating the details that go into a historical problem space analysis. The second part provides more analysis and conclusions about the game as a history.

Read more…Interactive History Class 2019 – Teacher’s Log #1 (Week of 8/19)

disclaimer: shockingly little/ sometimes no proofreading; I’m just trying to get the information and ideas out there fast.

So as some may know, I launched the second iteration of my Interactive History class, a senior elective at Cincinnati Country Day School. Last year it ran as a third quarter elective. While the class was very successful, I found it readily apparent that a reformed and expanded semester-long course could be even more successful. I had learned it was overly idealistic to suppose, in the first run of the course, that, say, reading one article on World War I would provide students enough refresher and new evidence to deeply critique a game on the topic. Hence the key difference (other than class time) in my approach this year: rather than encounter a briefer and necessarily more superficial investigation of the relevant history before playing a game, teach a small number of historical units in-depth and focus most of the games on these units. Then, arguably, students could learn and do history in a deeper more meaningful way through a variety of media and channel that learning into more rich and substantive play, analysis, and critique of historical games.

Who Am I? What Am I Doing Here? Player Agents in Historical Games

Adam Chapman and I are back on track debating the distinctions between different kinds of historical games and what makes a game historical. I find myself, in these kinds of discussions, increasingly referring to important distinctions I have found between types of player agents in historical games. I developed a starting taxonomy to make these distinctions explicit and useful for analysis in a talk I gave on Twine and interactive historical texts for the Value Project last year (The whole talk is worth it, I hope, but minutes 15:20 – 17:40 present my initial version of the taxonomy). I will write this up more formally in some articles in 2019, but since I have found it to be useful and I refer back to it increasingly, I wanted to present this to interested folk.

[1/1/2019 Note: I’ve gotten some helpful initial feedback, and rather than draft a new post, I am adding new sections in blue italics. This is all still very much a work in progress, but I became struck all-of-a-sudden by the idea of updating more interactively with feedback from Twitter — keep the thoughts coming!]

In historical games (whether using MacCallum-Stewart & Parsler’s (2007, 204) definition or Chapman’s (2016, 16) much broader definition) with historical problem spaces (McCall 2012, 2012, 2016, 8), the types of player-agents game designers focus on in their designs have a significant impact on the connections between the game and the past. There is, of course, a great deal of overlap, but it is still meaningful to consider four main types of historical agents in these games.

Civilization VI, Problem Spaces, and the Representation of the Cree – A few thoughts

PC Gamer published a short article on the controversy stirred by Civilization VI’s release of the Cree as a DLC civilization led by the historical leader, Poundmaker (Poundmaker Cree Nation leader criticizes Cree portrayal in Civilization 6). Reporter Andy Chalk quotes Cree Headman Milton Tootoosis’ assessment of the harmful depiction of the Cree:

PC Gamer published a short article on the controversy stirred by Civilization VI’s release of the Cree as a DLC civilization led by the historical leader, Poundmaker (Poundmaker Cree Nation leader criticizes Cree portrayal in Civilization 6). Reporter Andy Chalk quotes Cree Headman Milton Tootoosis’ assessment of the harmful depiction of the Cree:

“It perpetuates this myth that First Nations had similar values that the colonial culture has, and that is one of conquering other peoples and accessing their land,” Headman Milton Tootoosi said. “That is totally not in concert with our traditional ways and world view.”

“It’s a little dangerous for a company to perpetuate that ideology that is at odds with what we know. [Poundmaker] was certainly not in the same frame of mind as the colonial powers.”

And Chalk notes that Civ VI’s representation of the Cree as a playable civilization is problematic because it seems to suggest that the Cree were just another global player in the ultimate arena: world civilizations struggling to dominate the globe.

Numantia – Review

Numantia is a turn-based strategy game by RECOtechnology released for the PC, PS4, and XBox One. The game is set in the mid-second century BCE during the long, brutal wars the Romans fought in the Iberian peninsula as they conquered the region. Players can take the role of the Spanish or the Romans and play through a campaign that consists of a series of choice-based-text decisions on a stylized and attractive campaign map of northern Iberia punctuated by turn-based battles between Roman and Spanish forces on hex-based maps.

Numantia is a turn-based strategy game by RECOtechnology released for the PC, PS4, and XBox One. The game is set in the mid-second century BCE during the long, brutal wars the Romans fought in the Iberian peninsula as they conquered the region. Players can take the role of the Spanish or the Romans and play through a campaign that consists of a series of choice-based-text decisions on a stylized and attractive campaign map of northern Iberia punctuated by turn-based battles between Roman and Spanish forces on hex-based maps.

Read more…