Archive

The Possibilities of an Agential Problem Space Framework

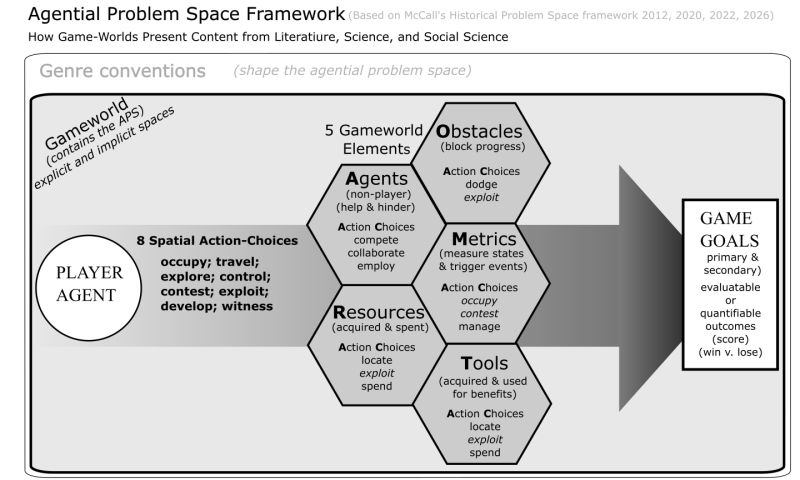

This is a quick post just to start a conversation and/or further work. It might be useful to notice all games with worlds can likely be helpfully be analyzed as Agential Problem Spaces, building off of the Historical Problem Space framework for analyzing (and thus thinking about designing) historical games–analog, ttrpg, and digital.

In origin, I proposed the Historical Problem Space Framework to point out that the ways Historical games characterize any given part of their history content cannot be considered independently from that parts functional role in the game’s historical problem space. https://www.playthepast.org/?p=2594

And that developed into a full framework that is still developing (even into current book project, Designing Historical Games for the Classroom). Bottom line, though, is that systemically functional nature of games about worlds–regardless of whether those worlds are fictional historical etc.

https://gamestudies.org/2003/articles/mccall

So any game with a world (and inhabitants if that’s not understood) can be analyzed using something like the Historical Problem Space framework. I really have not had time to explore this in detail, but I’m going to start referring to it, for consistency and connection to HPS, as an Agential Problem Space.

Now, I’m a historian and a history teacher and a historical game designer and a historical game studies academic. I do NOT have ANY substantial grounding in (post Roman) literature or literary theory. So when I speculate next, why seeing games as agential problem spaces might be useful, it is based on my perspective in all those areas listed in the last paragraph

So since HPS is also a theory for how games shape historical content maybe? an Agential Problem Space framework for literature-based game studies interested in how game designer present a world in their game that is

1) based on a literary / text lore corpus

2) purporting to be the “real world” or a “real historical world”

Because then an Agential Problem Space can help with terms and tools for seeing how a game medium shapes literature and lore and perceptions of the world into a game, which basically means a medium that is structurally like an historical game. ???

I also think an Agential Problem Space framework might? be very helpful for teachers in other disciplines than history, not least of all lit & lang (but any subject that purports to represent the world: science, social science, etc.) As an approach to how they & their students could design world-based games in their areas?

What do you folks think?

New set of print and play prototypes for history classes

In a flurry of posting productivity on Gaming the Past, I added a new project this morning. The prototype (still in need of work but playable) for Rhetoric and Revolution. This is a card game about the political competition around drafting the 1791 constitution. (#3 on the page). As always, please send me any and all constructive feedback. These are early works-in-progress. But the 3 listed have all been tried in some form or other with students and can be a good learning activity (so long as your class reflects and criticizes them at least a little!)

https://gamingthepast.net/tabletop/jeremiahs-prototypes/

Paradox Europa IV Universalis Educator Guide is Out (and Free)

I’m very pleased to share Paradox’s Educator’s Guide for Europa Universalis IV (that I wrote) is now available for all. EUIV is a challenging game & I spent considerable time breaking down exactly how I’d use it in history classes in hopes the many interested educators out there will give it a try.

It’s a 3 part guide: Logistics, Student initial play guide, and historical problem space analysis of EUIV. The focus is on the game as history so interested educators can decide what parts they want to focus on and what aspects of the history are more and less problematic in the game.

Hopefully it will be of some use out there. I enjoyed the challenge, and I am very glad to have a worked example out there for educators about how to use the historical problem space framework for teaching. Of course, as always, just reach out if I can help you further or reach out to Paradox.

Gameworld Space and Action-Choices in Historical Games (HPS framework)

Just a quick reminder/introduction. The Historical Problem Space framework is a set of terms and concepts I’ve been developing over the past decade+ to help all intersections of educators and academics analyze historical video games in away that is holistic and recognizes that historical games are both functional as working computer programs (and, to a lesser but still useful extent, analog games) and as cohesive designs. This means any particular historical phenomenon in a game is functionally and cohesively connected to al the rest of the game design.

The framework continues to develop but my most recent core writings on this are:

The Historical Problem Space Framework: Games as a Historical Medium (2020)

Gaming the Past: Second Edition (2022)

And there are links to other articles and talks about HPS on this page

Greetings to all who, like me, find themselves fascinated by historical games,

Not infrequently I find my thoughts well ahead of my writing on the Historical Problem Space framework for historical game analysis (https://gamestudies.org/2003/articles/mccall) (Yes, I’m that sort of person who thinks about games and history games a significant amount of the time) Today I was working out a lecture on 4x games so that my students will have some genre understanding when looking at Colonization and Imperialism (the 4x games — but of course the historical phenomena too). I’ve been referring to the different kinds of action-choices a player agent can make in gameworld space.

I have listed and briefly discussed some of the core action choices a player agent has available in a gameworld space. I thought I had perhaps listed them all in the 2020 article, or perhaps in GTP 2.0 but now I’m thinking the core action-choices in gameworld space should be (helpfully, I hope) set out in one places until I can work them into a published article or book.

So, a quick reminder, the gameworld space is the space in which the player agent (the main playable character) pursues the goals (if they choose) that the developers have set for them and, while doing so, encounter the various elements in the space (a.r.t.o s = non-player agents, resources, tools, obstacles etc). The player agent makes and takes action choices in order to (if they choose) attempt to achieve the goals the developers have designed for the game. The “problem” in the historical problem space design that is standard in historical games, is to solve, avoid, overcome, utilize etc. the elements (a.r.t.o s) in the gameworld space that are keeping the player agent from the designed goals or can help the player agent.

Gaming the Past, Second Edition, Is Published

Gaming the Past, Second Edition, is out with Routledge! I am so very grateful and excited to have had the chance to revise significantly and add to the first edition work that came out over a decade ago. If you’re interested in reading more about my bibliographical road to Gaming the Past First Edition and the decade between it and 2.0, I’m working on a series of posts about my time in historical game studies as one of the earlier academics.

— Jeremiah McCall

18 Years in Historical Game Studies: A Biographical/Bibliographical Musing Part 1 (2005 – 2012)

Gaming the Past, Second Edition, is out today with Routledge! I am so very grateful and excited to have had the chance to revise significantly and add to the first edition work that came out over a decade ago. I thought perhaps it is a good time to reflect a little on my time and work in Historical Game Studies and in teaching history using video games as tools. Here’s a first post to see if it’s of interest to anyone else.

— Jeremiah McCall

Though I experimented a little with interactive learning in history in my graduate years finishing my PhD on Greco-Roman History with Nate Rosenstein at the Ohio State University (2000), I did not work with making and integrating actual physical games until my first history teaching position in a secondary school. Hoping very much to add life to my ancient history courses (high school) I made a couple of physical game prototypes: One a simulation of Roman politics in the Republic and the other a simulation game of ancient warfare. For students, the interest these games brought to the areas we studied was palpable, and I knew I wanted to do more with games in history education. This process continued when I came to Cincinnati Country Day School and had access to laptop computers. I experimented with some board games like Diplomacy and continued to work on designs for tabletop prototypes–many never reaching a truly playable state. I was struck along the way with the amount of research I had to do to make a historical game. Inspiration–get students to design games as a way to encourage them to study a historical topic in depth. This led to my first “Historical Simulations” senior elective at CCDS, in the winter and spring of the 2004-05 school year. While the course was focused on having students design their own historical tabletop games I was also struck by Civilization III as a potential model to play and study. So, in addition to the design part of the class, I had students play Civ III and compare it to the first chapter or so of Patricia Crone’s Pre-Industrial Societies. This experiment with Civilization (III) caught the attention of friend and colleague Kurt Squire (now UC Irvine) who invited me to speak at the Education Arcade in May of 2005. I was part of a panel discussing the use of Civilization III in the classroom. There’s still a video of the whole panel to be found on Youtube (and me considerably younger with a great deal more hair.)

Read more…Mobile Civilization Building Genre (Draft)

I wrote this section on MCB games for the genre chapter Gaming the Past, Second Edition, but had to cut it for reasons of space. Just posting it here in case it’s of interest

A somewhat more unique mobile genre is the Clash of Clans clear mobile genre (we’ll call “mobile civ games” for short) These games are clear examples of the freemium game model where players may play for free but get access to extra abilities, resources, etc. if they pay money to the developers through microtransactions. In games of this genre, the player agent leads a civilization—from a list of historical states whether Roman, Chinese, Aztec, or any number of other options depending on the game. The player agent constructs settlement in a home-base location with some geographic features: generally open land and land that must be cleared to be developed upon. The player agent fills their home-base settlement with various types of buildings. The core buildings are houses, each supporting a limited number of workers for the player agent. These workers then construct all the other buildings of the civilization. Buildings range in function from barracks to resource storage to defense to research.

There tend to be a small number of standard resources in these games, two or three: often food, coins, and wood or stone. These are stored in stockpiles with finite capacities in the player agent’s settlement. Resources are sometimes gathered automatically by the civilization when the player is logged out; sometimes the player must log in to gather resources, a design technique to encourage players to regularly visit the game and keep up the player base. If the player agent’s resource stockpiles are full, all additional harvesting of those resources is stopped until the player logs in and spends the resources. So, for example, if the player-agent’s food stockpile is full, all additional incoming is wasted, a lost opportunity, and the player will need to log in and spend food on some project to avoid missing out on acquiring resources. Indeed the whole game is designed around real-world time consumption and players can decide whether they want to commit more real-world time to the game, logging in and playing more frequently, and, as the level up, waiting longer and longer times to construct more powerful buildings and armies, or purchasing special resources with real-world money to cut down on time.

Read more…Historical Problem Spaces on the Studying Pixels Podcast

In late September, I had the pleasure of talking with Stefan Simond over at the Studying Pixels podcast about games as historical problem spaces

https://studyingpixels.com/games-as-historical-problem-spaces-with-jeremiah-mccall/

An Introduction to Historical Problem Spaces

This is a reprint of my original PlaythePast post . It offers a brisker survey of the Historical Problem Space framework that I lay out in greater detail in the academic journal Game Studies article, The Historical Problem Space Framework: Games as a Historical Medium, also published in late 2020. The ambition to write a series of these for PlaythePast.org has not yet been fulfilled.

I’m returning, happily, to my roots to write a series of essays on PlaythePast. In 2012 I proposed the outlines of a framework (first here on PtP and then elsewhere in The Journal of Digital Humanities) that I have come to call the “historical problem space framework.” Since then, I have spent a considerable amount of time–both as a history educator who uses historical games and as a historian studying games–developing and refining this historical problem space framework. While I have an article in the works on the subject, and regularly make use of it in my classes and research, the framework has developed considerably since I first proposed it 8 years ago. Someday, perhaps I’ll get to write a book on the topic. But for now, in hopes of providing a hopefully easy-to-understand, holistic, and practical approach to analyzing and explaining the history in historical games, I’m writing a series of essays here on Playthepast, where the concept was born. Hopefully, readers will find the framework useful for their own research, teaching, and design and just for thinking more about how historical video games work. This is a work in progress and comments, questions, and constructive criticism are most welcome.

The historical problem space framework (HPS) is a holistic, medium-sensitive, design-focused framework for analyzing and understanding, designing, and teaching with historical games. It is, above all, meant to focus practically on how designers craft historical games, based on an understanding that games are mathematical, interlocking, interactive (playable) systems.

History is, in broad terms, the curated representation of the past, so pretty much any medium that can communicate ideas about the past can function as history. This is as true for video games as it is for texts, images, cinema, and so on. It is critical to understand, however, that each medium has its own characteristics, its own ways of presenting the past. This point has been made increasingly clear by historians studying historical film and is certainly true of historical video games. Both need to be approached not as a deficient forms of textual history, but as media that are simply different from text, talk, or lecture.

Read more…New Encyclopedia Article – History Games

My encyclopedia article, an introduction to historical video games and historical game studies has just been published as part of the open-access online Encyclopedia of Ludic Terms